Solon’s Seisachtheia definition

The term is a complex word from ancient Greek, from "seio" (shake) + "achthos" (weight, debt ). It basically meant "to shake off the weights".

In ancient Athens, Solon's legal regulation of debt became known as Seisachtheia. By this law, all debts were written off, and all slaves were set free.

In the late 7th - early 6th century BC, some Athenians were forced to cede their land to wealthy landowners, to whom they had to pay rent in the form of a portion of the goods produced. As Solon himself informs us, the legislation of Drakon allowed the citizen, whenever necessary, to pledge with himself. However, if the terms of the agreement were not observed, he risked being enslaved and sold out of his city (Pausanias, Attica 16.1, Solon, Excerpt 36, Aristotle, Athenian State 12).

The economic situation of many poor Athenians who had no political power was constantly deteriorating and many of them had already been sold as slaves. This situation led to an economic and social crisis that Solon when he was elected ruler in 594/3 BC, tried to alleviate. One of his most important economic reforms was secession and the categorization of political privileges based on each citizen's property.

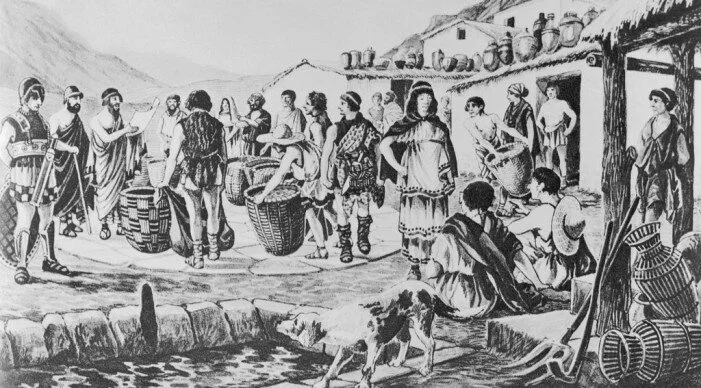

Athenians pay taxes in ancient Greece

With the "Seisachtheia" Solon managed, as he claims, to "shake off" the burden of debt from the shoulders of the poor peasants. Some scholars have linked this measure to all those who had borrowed and cultivated the lands of the rich and powerful with the pledge of their personal freedom ("bodily" borrowing).

With the "Seisachtheia" the debts were canceled and all Athenian citizens who had promised to produce and give a part of their harvest were released. Those who had ended up as slaves in Attica because they were in debt were set free and those who had been sold as slaves outside Greece returned to Athens (Aristotle, Athenian State 6, Plutarch, Life of Solon 15.3-5).

In particular, in order to push the previous institution out of the public consciousness, Solon removed the terms, the stone or marble slabs that marked the boundaries of farmland and at the same time indicated that the cultivator had no right to property and recalled the obligations of the poor peasant to his owner. They usually had a short inscription indicating the function of the term.

Agriculture, a common use for slaves, black-figure neck-amphora by the Antimenes Painter, British Museum

He brought back those who had been sold legally or illegally outside Attica, and those who had left Athens out of necessity and especially because of their debts. He also brought back the families of those who had been sold or exiled, who had followed them from the first moment of their expulsion from Athens.

But there were also cases of families who were later exiled since the rulers had the right to punish the descendants of the accused in this way, even if he was no longer in the city. So if a whole family left the city, their land was confiscated and was no longer available.

While this provision allowed them to return and regain their civil rights, it did not guarantee them the return of their old land or the acquisition of another land in place of the previous one. Finally, Solon freed those who had been enslaved in the city with the Amnesty Law.

After the "Seisachtheia", the next step was to divide Athenian citizens into social classes based on their income from the production of grain, olive oil, and wine (Aristotle, Athenian State 7, Plutarch, Life of Solon 18.1-3).

Thus, the population of Athens was divided into four classes, each of which possessed specific political privileges. Membership in each class was determined by each citizen's wealth, which was based on a fixed measure of annual agricultural production in grain or wine, the "medimno" and the "meter." Athenian citizens belonged either to the five hundred medimnos(500 medimnos or more), to the three hundred medimnos(from 300), and to the two hundred medimnos(from 200). Finally, those who had a fortune of fewer than 200 medimnos per year, or none at all, belonged to the thetans.

The result was that the nobility was gradually replaced by an aristocracy of the wealthy, as participation in the new class now depended on economic change. Any financially successful Athenian could join the privileged ruling class, while those who lost their wealth in one way or another ceased to belong to it. Power belonged to those who excelled in land wealth.

Solon defends his laws

In addition to the two measures mentioned above, there are references to some other financial decisions of Solon, but these are not considered credible. Plutarch mentions in the "Life of Solon" that the Athenians of his time maintained a tradition according to which Solon had fixed a much lower price for wheat. Lysias, in one of his speeches in which he refers to the term "interest", connects its introduction with Solon. It is considered very likely that Solon sought to use the interest to offset the consequences of "Seisachtheia". The deprivation of the ability to enslave those who owed him money was covered by the assurance of the lender's right to draw interest.

The most important result of Solon's economic reforms was that they freed landless citizens from the fear of possible enslavement (Pausanias, Attica 16.1). As a result, most Athenian peasants became independent micro-landowners.